Dec 9, 2025

What happened in the Nipah Protein Design Competition so far?

This competition marks the third time we have challenged the community to design binders, with this edition focused on targeting the Nipah virus. In this blog post, we provide a short overview of the submitted designs, examine which design methods were most widely adopted, and highlight several noteworthy and creative community contributions.

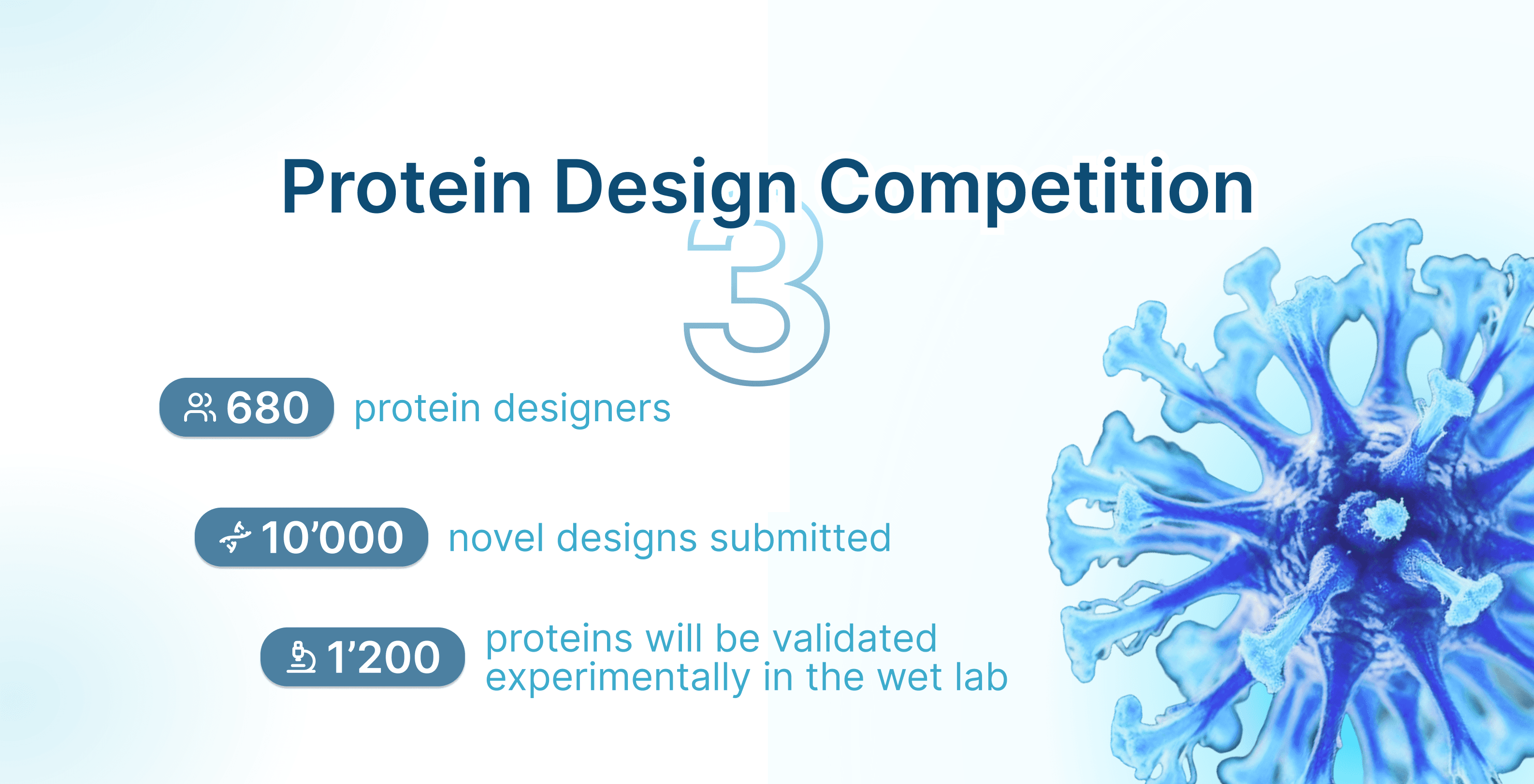

After a busy few weeks with over 680 protein designers submitting their best binder designs against the surface glycoprotein of the Nipah virus, the submissions and community vote doors have closed and we are waiting in anticipation for the experimental results to arrive. In the meantime, we want to highlight some interesting new insights and cool protein structures that we have gathered during the course of this competition.

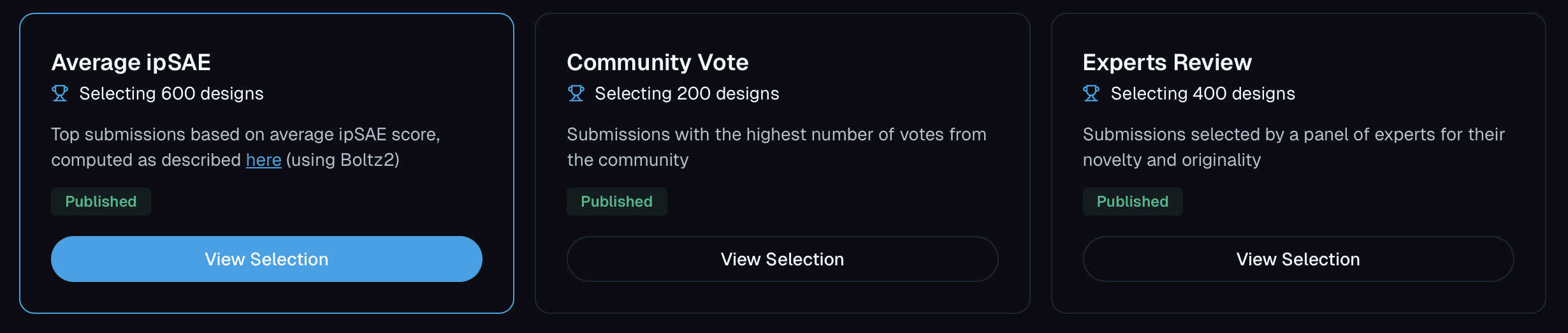

Specifically, participants were asked to create binders that can disrupt the interaction between the viral glycoprotein G and its human receptor, ephrin-B2/B3 - an essential step the virus uses to enter host cells and initiate infection. Out of the thousands of designs submitted we wanted to select the 1 000 most promising designs for experimental validation. 600 designs were chosen based on the best Boltz-2 ipSAE score, 300 were selected by the community vote and another 400 by a panel of protein design experts. In total, more than 1 000 binders are being tested in our lab right now for binding to Niv-G. So stay tuned for the results of the competition, which we will release on January 13th on Proteinbase!

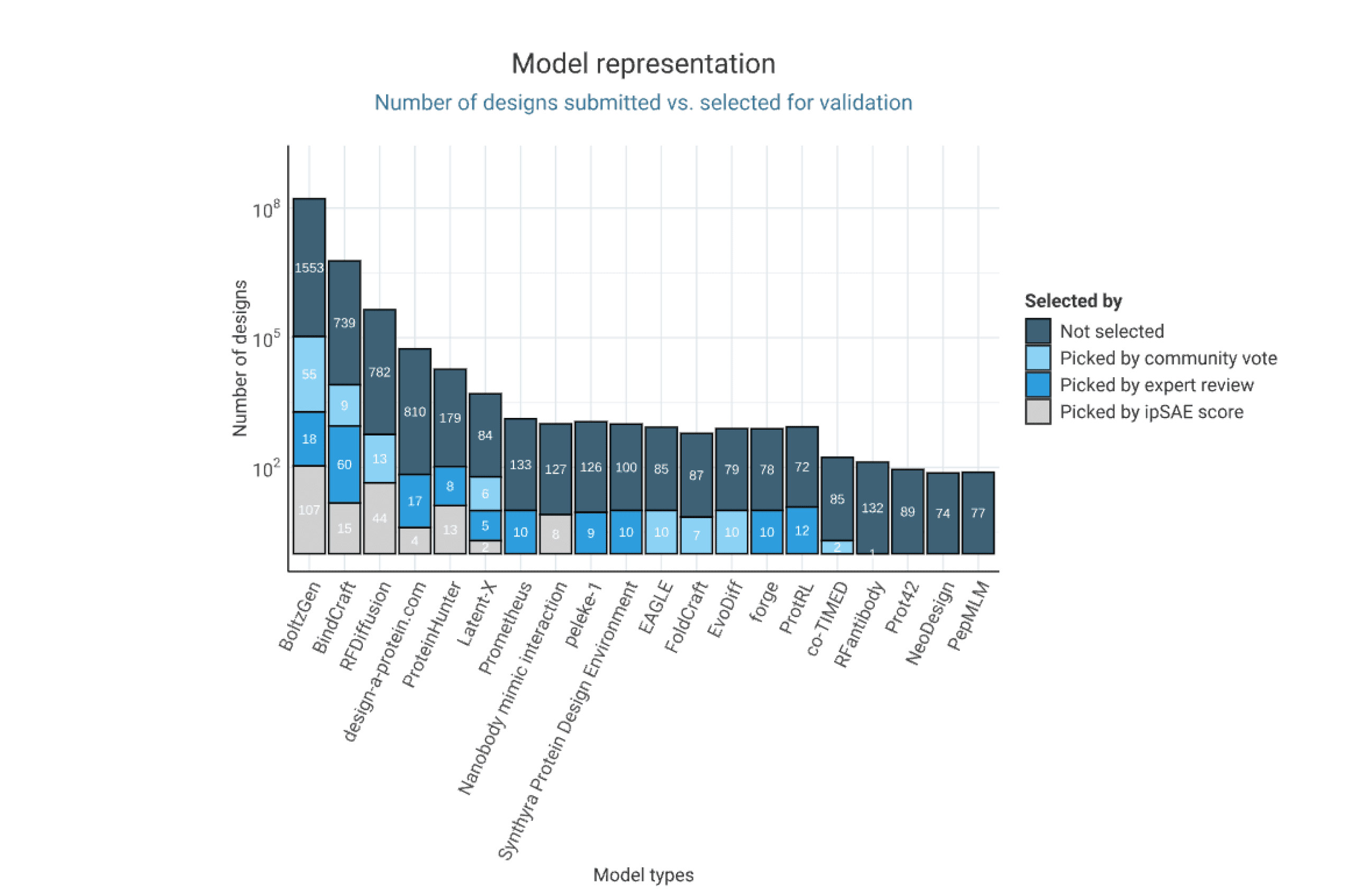

Four design models dominate the competition

Mirroring the trend we observed in our previous binder design competition, participants relied heavily on RFDiffusion and BindCraft to design their binders. However, the design toolkit is evolving and in this latest competition, the newly launched BoltzGen model (Stark et al.) emerged as the most popular design tool. We’ll explain the top design choices in more detail below.

BoltzGen is an all-atom generative diffusion model that unifies structure design and prediction into a single framework. By embedding structural reasoning directly into the generative process, the model achieves state-of-the-art accuracy in both design and folding. The model was validates across 26 targets in eight experimental campaigns, reaching a 66% success rate for designing binders with affinities in the nanomolar range. BoltzGen unifies the traditionally separate stages of design, inverse folding and filtering into one streamlined pipeline. This ease of use might also explain why the tool was very popular among designers.

We developed the platform design-a-protein.com specifically for this competition. It prioritizes ease of use, allowing non-experts and beginners to explore protein design in a playful way rather than aiming for optimal results. Users can generate Nipah virus binders by selecting structural hotspots on the viral protein, which serve as input to the design pipeline. Protpardelle-1c (Lu et al.) generates 3D binder backbones around these hotspots, and ProteinMPNN (Dauparas et al.) is used to designs sequences that fold into these structures. Additionally, users can control parameters such as chain length, number of designs, and temperature, and inspect predicted ipSAE scores in a dashboard to easily select high-scoring candidates.

The animation below shows the cumulative growth of submissions throughout the competition. Many participants submitted multiple entries over the course of several weeks, and momentum clearly built over time, with a sharp increase in submissions as the deadline approached.

Optimizing ipSAE score from Boltz-2

As in the previous competition, the design of this challenge is based on preselecting designs for validation using an in silico metric. This naturally fostered competition for the top spots on the leaderboard. The leading ipSAE score changed repeatedly over the course of the competition, with participants actively pushing the limits of this metric. This led to a steady upward trend in the highest-scoring ipSAE designs submitted over time. Competition intensity was high, with some participants even opting to experimentally test their top in silico candidates experimentally before submission, aiming to ensure that only the most promising designs were entered (here).

Let’s take a closer look at the top 100 binders

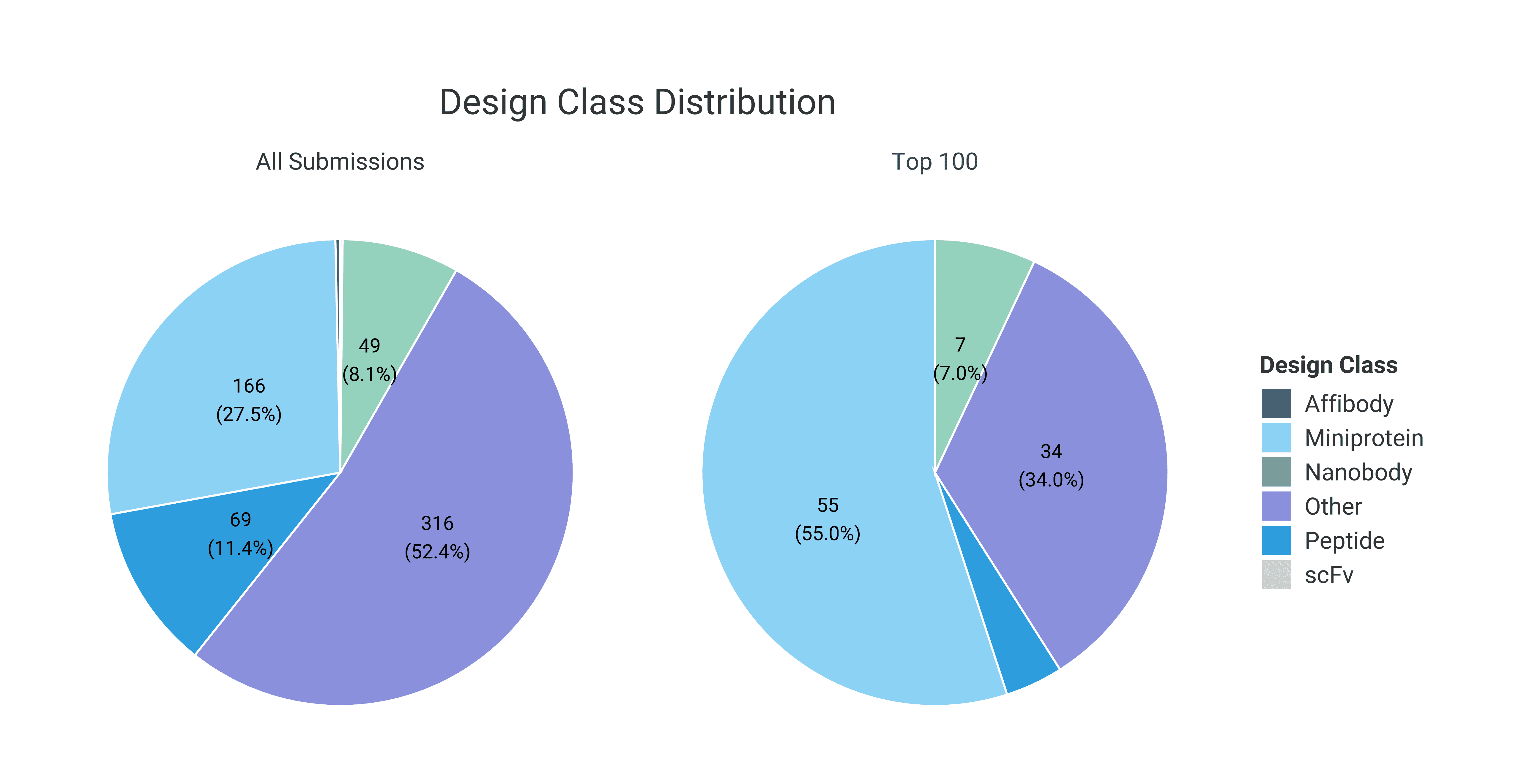

When comparing the molecule types between all submissions with the top 100 designs ranked by ipSAE score, miniproteins are approximately twice as prevalent in the top-ranked set, accounting for 55% of the top 100 submissions. Miniproteins are defined as peptides with a molecular weight below 10.5 kDa and less than 35% loop content. This enrichment is consistent with the tendency of Boltz-2, when used without a template multiple sequence alignment (MSA), to favor de novo miniprotein designs rather than antibody derivatives such as nanobodies and scFvs (Yin et al.).

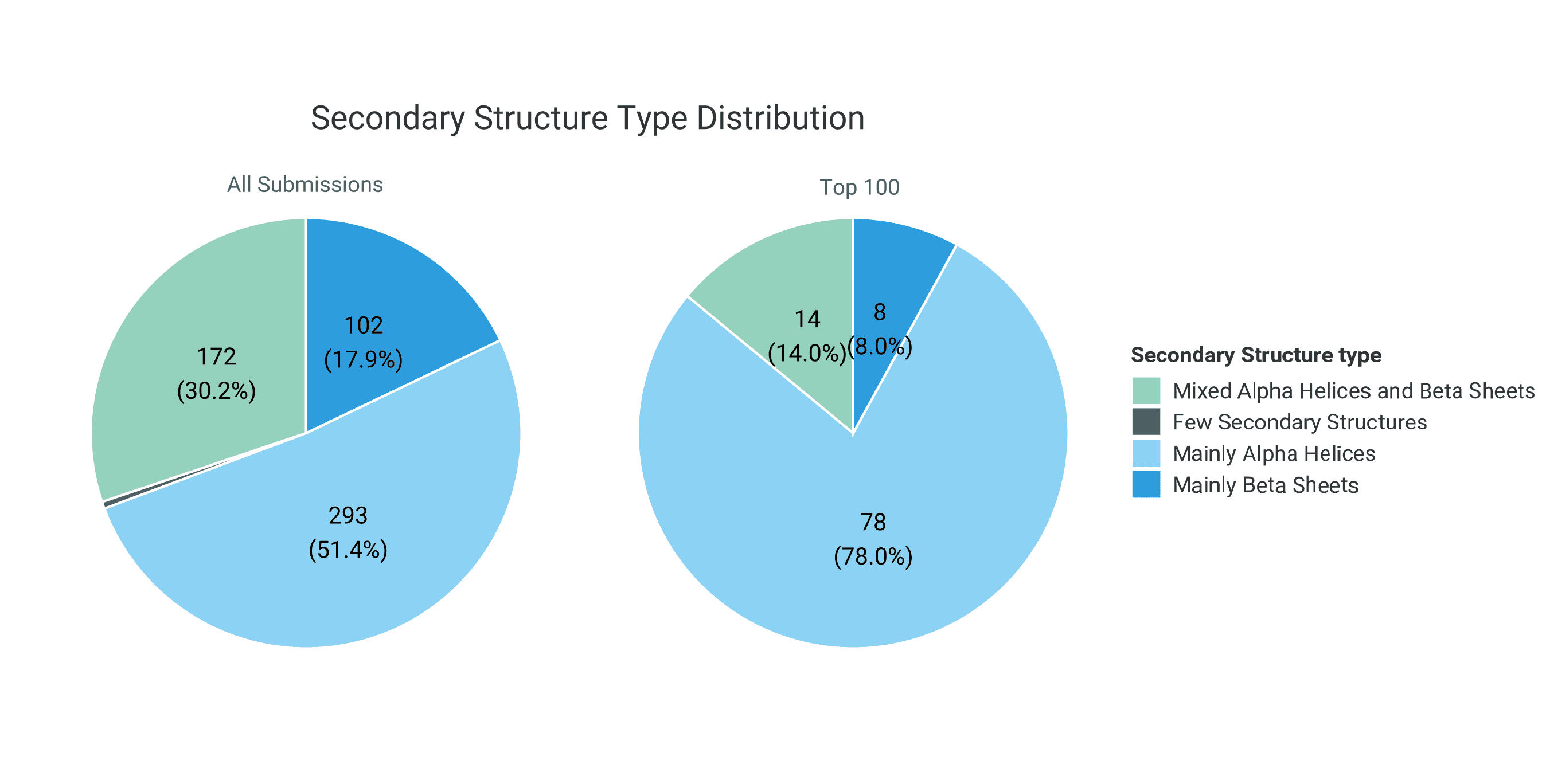

Interestingly, the top 100 designs are enriched for proteins dominated by α-helical structures compared to the full set of submissions. Correspondingly, designs containing mixed α-helical and β-sheet architectures, as well as predominantly β-sheet structures, are underrepresented among the top-ranked entries. This shift may reflect the greater fold stability and lower structural ambiguity of α-helical proteins, which can lead to more confident structure predictions and higher ipSAE scores.

Choosing a good computational filtering metric

Previous competitions have shown that choosing an appropriate computational score to prioritize the most promising designs for experimental validation is in itself a challenge. Previously, we had used either the interface PAE (iPAE) metric from AlphaFold2 or a combination of iPAE, AlphaFold2’s interface pTM (iPTM) score and ESM2’s log-likelihood score (ESM-PLL). Both turned out to have their shortcomings. In the last competition, our use of unnormalized ESM log-likelihoods created a bias toward shorter designs.

For this competition, we opted to use the Boltz-2 ipSAE score for filtering and selected the 600 most promising designs based on this metric. You can find our reasoning for choosing it in the FAQ. Already during the course of the competition, some interesting questions and concerns were raised regarding the reliance of this metric.

Many participants evaluated their designs locally prior to submission and encountered reproducibility issues of the ipSAE score. These differences arise in part because the model can yield slightly different results depending on hardware configuration and random seeds. A certain degree of unpredictibility was intentional, as it makes direct optimization for the metric more difficult. However, as it turned out over the course of the competition, the ipSAE score variance was not uniform across designs and therefore problematic. Importantly, variability in ipSAE reproducibility may also have conferred an unintended advantage to designs with more stable scores, as these could be more easily optimized directly for the metric.

Given the difficulty of choosing a universally robust scoring function, we wanted to complement the computational filtering with community input and expert knowledge when deciding which designs would ultimately be selected for experimental testing. We’d like to sincerely thank the community for enthusiastically participating in the community vote, championing their favorite designs, and generally making this process far more interesting than a simple ranking table. We also owe a big thank-you to a group of protein design experts who volunteered to dive into the submissions and hand-pick proteins they found particularly promising.

This combination of computational scoring, community engagement, and expert review was intended to mitigate the limitations of any single selection strategy and to arrive at a more balanced and informed set of designs for experimental validation. Additionally, to mitigate the impact of ipSAE reproducibility issues, we added 100 additional expert-selected sequences to the pool of designs designated for experimental validation.

Nipah Gallery

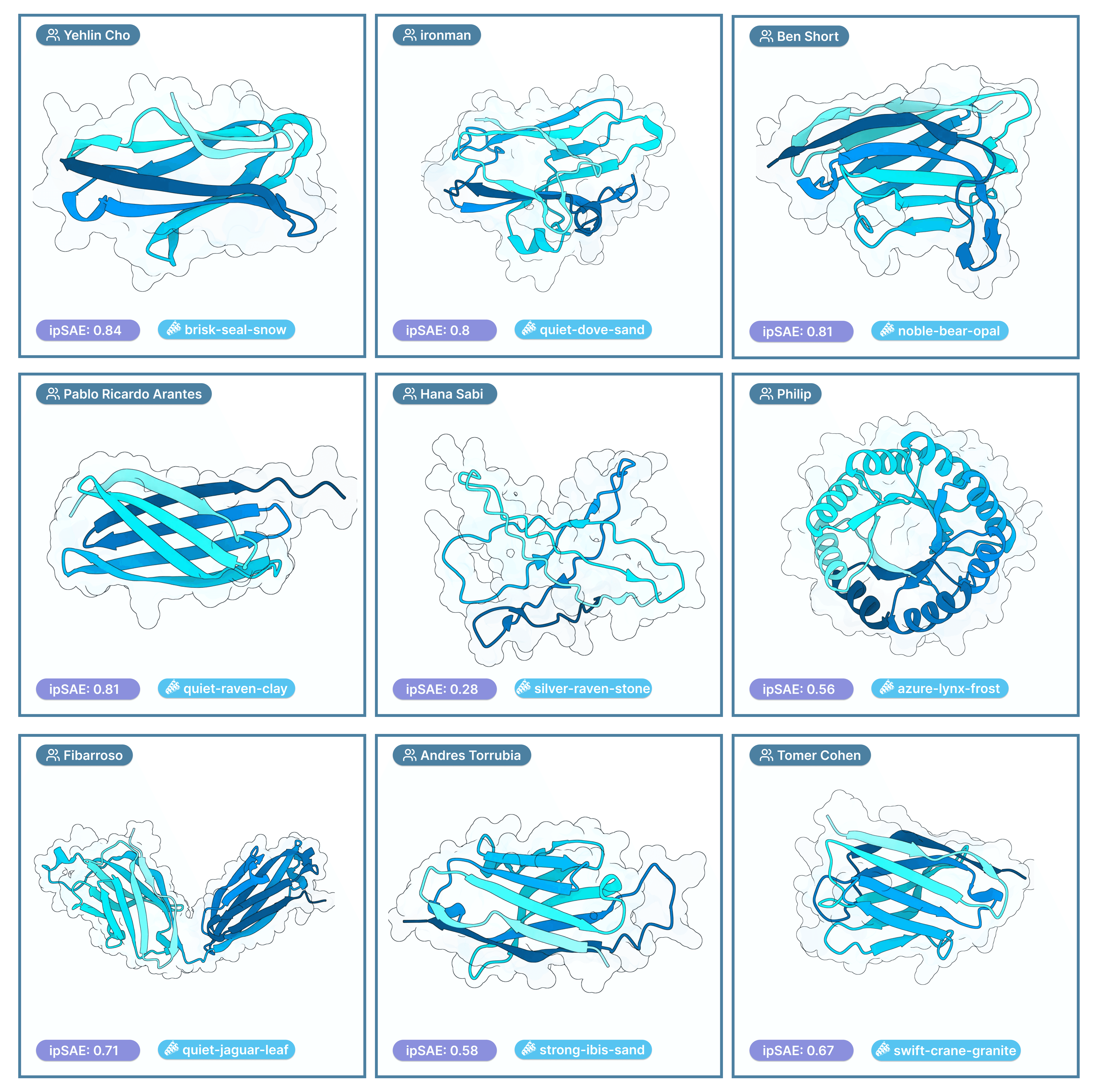

Welcome to our mini “Nipah Gallery” — a highlight reel of protein structures we found particularly interesting from this competition. Each image links directly to its Proteinbase entry. Think of it like “Spotify Wrapped” for our Nipah design competition. The featured designs were selected based on how unique and compelling the structures were, the creativity of the design approaches used, and our collective intuition as the Adaptyv team about which candidates might express well and bind effectively.

Highlighting some cool approaches and community efforts

Some of the most interesting competition submissions are those that offer insight into the design process, including the decisions, motivations, and reasoning behind them. We’d like to thank everyone who took the time to talk about the strategies. We believe this contributes to the collective understanding of protein design tools quite a lot! In the following, we highlight several of these submissions, along with blog posts and social media discussions that reflect participants’ experiences during the competition.

Andrés Torrubia learned firsthand that aggressively optimizing leaderboard metrics does not necessarily translate into experimental success: although his designs ranked #1 in silico in the EGFR competition, they ultimately failed in the wet lab. In this competition, he adopted a markedly different strategy, imposing constraints on compute and intentionally avoiding direct optimization of the ipSAE score in order to mimic a more realistic therapeutic design workflow. Check out his submission here.

Several members from the Wells Wood lab took part in the competition and employed different design strategies and models. But they all assessed their designs using molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate the stability of the receptor–binder complexes. Final candidates were then ranked using a custom DE-STRESS–based score to identify the most promising designs. As a result, two team members finished in the top 100, including Leonardo Castorina who secured the top position on the leaderboard. He generated a large set of designs by combining BindCraft with TIMED sequence generation, large-scale sampling, and Boltz-2–based evaluation, followed by surrogate modelling and one round of in silico directed evolution.

Yehlin Cho did not only rank 14th on the learderboard with her designs but also created an interactive site to demonstrate how the Boltz-2 ipSAE and ipTM scores compare to the corresponding metrics from AlphaFold3. This comparison further underscores how strongly such metrics can vary depending on the prediction tool used and the specific protein sequence being evaluated. Check out here super intuitive webpage that also allows you to look at your own data by simply uploading them as a CSV file.

Ariax Bio submitted both nanobody and miniprotein designs to the competition and also created an excellent tutorial for getting started with protein design using BoltzGen. The tutorial walks through all the key steps required to run a design campaign and highlights the most important aspects to pay attention to along the way.

Jacob DeRoo documented in detail his design decisions and released his code here. He tried different design modes using BoltzGen, from free design, to motif grafting and hotpot/binding site specification. He also experimented with RFDiffusion, ProteinHunter and BindCraft.

In their submission, Silico Biosciences used their own peleke-1 suite of antibody language models to generate heavy and light chain Fv sequences conditioned on an epitope-annotated antigen. In their blogpost they highlight their issues with reproducibility of ipSAE scores and show that ipSAE scores fail to correlate with physics-based estimates of binding affinity. Highlighting again the need for more robust and reproducible scoring methods and good benchmark datasets for the field.

We’d like to thank all participants the Nipah competition, the people who voted for their favorite designs, our panel of experts, and everyone else involved who made this such a cool experience. We’re super excited to release all the experimental results and reveal the final rankings in January!